Ulrike Bahr-Gedalia

Technology, Business and Public Policy Executive and a member of The Canadian Internet Society’s (TCIS) Policy Committee

Brent Arnold

Principal at Capstan Legal and Board Chair, The Canadian Internet Society (TCIS)

Canada is no longer facing incremental technological change; we are facing a whole-of-society transformation, and it won’t wait for the legislative process to catch up.

The decisions we make now will determine whether Canada emerges as a sovereign leader in the AI era or slips into deeper technological dependency. We must choose between building our own infrastructure, governance models, and workforce strategies, or depending on the ones built and controlled from elsewhere. The federal government’s latest announcements are a good start, but without bold follow-through, Canada risks becoming a client state in the AI-powered world economy.

In this interview, Ulrike Bahr-Gedalia, Technology, Business and Public Policy Executive and a member of The Canadian Internet Society’s (TCIS) Policy Committee and Brent Arnold, Principal at Capstan Legal and Board Chair of TCIS, discuss why Canada needs to be bold in its actions, follow through and decide whether we will take charge and shape our AI future, or have it shaped for us. The time to decide is now.

Ulrike Bahr-Gedalia: Canada is at a pivotal moment. How would you describe the current “lay of the land”?

Brent Arnold: Canada’s early leadership in AI (marked by the 2017 launch of the world’s first national AI strategy) is no longer sufficient. While recent steps, such as Minister Evan Solomon’s appointment as the first Minister of Artificial Intelligence and the establishment of a 26-member AI Strategy Task Force, are promising, they are only a better-late-than-never start.

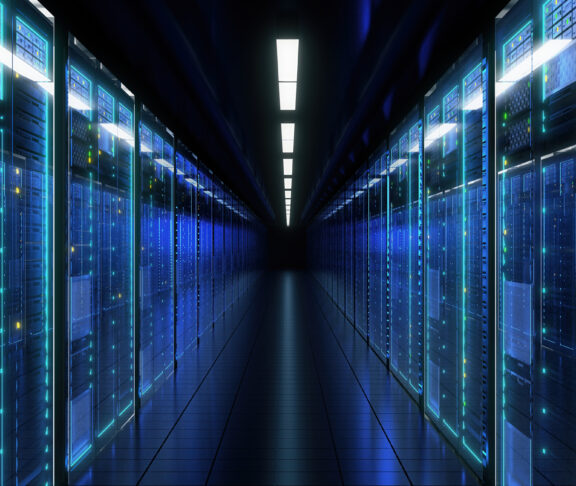

The evolving AI ecosystem is indifferent or hostile to Canadian control. Microsoft’s 2025 declaration that U.S. law supersedes Canadian sovereignty obligations exposed the extent of U.S. hegemony in this space, while the recent AWS outage affecting Canadian services reminded us how dependent we are on too few platforms. Our dependency on foreign digital infrastructure has become perhaps our greatest strategic weakness.

Bahr-Gedalia: Sovereignty is a much-discussed term. How would you define sovereignty in the context of our discussion, bearing in mind that sovereignty implies control, not isolation?

Arnold: Canada’s path forward must be grounded in digital sovereignty: the ability of our governments, businesses and institutions to control their digital futures. That means more than data sovereignty (i.e. keeping data on Canadian-owned servers on Canadian soil); it means ensuring AI systems deployed here reflect Canadian values, operate under Canadian laws, and serve Canadian interests.

Encouragingly, the federal government’s $2 billion Sovereign AI Compute Strategy signals a recognition of this. This, too, is a promising start, but just a start. True sovereignty requires domestic cloud infrastructure, open and interoperable models, and Canadian-led AI development across high-stakes domains like health, defence, and public safety.

Bahr-Gedalia: We can’t regulate what we don’t understand. Does that ring a bell?

Arnold: Indeed. Canada’s current regulatory frameworks, including privacy and consumer protection laws, are outdated and fragmented. The lack of comprehensive AI legislation (after the stalling of the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act) leaves businesses in limbo, unsure how to innovate responsibly, or whether they have already incurred liability. The government must fast-track risk-based governance measures that include clear definitions, accountability structures, and proportional requirements.

But this is not just a legal issue; it’s a coordination challenge. We need a whole-of-government approach to AI, with consistent standards across departments, clarity on enforcement, and room for agile response to rapidly evolving technologies.

Bahr-Gedalia: What about the workforce? Are we ready (yet)? AI adoption not only moves at the speed of trust, but also at the speed of AI literacy.

Arnold: Despite warnings from the tech and policy communities, Canada still lacks a national retraining strategy for the massive disruption AI is about to cause. That disruption won’t be confined to the blue collar sector; it is already displacing junior lawyers, financial analysts, customer service workers, computer programmers and even cybersecurity professionals.

We need comprehensive, publicly funded retraining programs, designed for working adults, integrated with income support systems, and focused on skills that complement rather than compete with AI. AI may increase productivity, but if Canadians don’t share in those gains, we risk deepening inequality and losing public trust.

Bahr-Gedalia: What about public procurement? Would you agree that procurement is a policy?

Arnold: Absolutely. In fact, perhaps the most overlooked but immediately actionable reform is in public procurement. Government procurement decisions are industrial policy in disguise. Yet Canadian AI firms continue to be shut out in favour of large, often foreign, incumbents. If Canada wants to grow its AI sector, we must build pipelines for domestic innovation into government systems.

That includes SME set-asides, fair risk assessments, and procurement guidelines that reward sovereignty, not just size. For our future’s sake, we need to stop asking “Is it the cheapest?” and start asking “Does it strengthen our digital ecosystem?”

Bahr-Gedalia: What’s the conclusion? Build partnerships, but on our terms?

Arnold: Canada must deepen partnerships with democratic allies, especially in Europe, Israel, and Asia, to counterbalance U.S.-dominated AI platforms. These alliances should include co-development of AI technologies, coordinated governance approaches, and shared infrastructure that reflects shared values. We don’t (and, almost certainly, can’t) do it in isolation, but we must forge partnerships that don’t again imperil our autonomy or concentrate our risk.

Minister Solomon has rightly said that we are at a moment of transformation, not tinkering. He is correct. Canada must choose: Will we shape our AI future, or have it shaped for us? The choice is still ours, but the window is closing.

For more information on The Canadian Internet Society, visit internetsociety.ca.